When we know WHY and HOW to choose peace. Would we still choose war?

The article from the Washington Post: „The secret to disagreeing with people from 20 different countries, in one chart“ made me think about the conflict resolution in the international context. Does not matter if you use the chart as a paradigm for cross-national comparisons or criticism it harshly. My point here does not refere to the validity of the dimesnions. I am interested in understanding and … solving problems.

I truly believe that whether it be interpersonal or between nations, a conflict is always a stressful experience, but it also has the potential for an evolution for the better.

When most people are asked whether they enjoy conflict their typical response is, “no,” and their look is one of distaste in remembering past conflicts, or surprise at why I would even ask such a question. I’ve been passionate with the field of Conflict Resolution since I’ve experienced that “resolving a conflict” can mean so much more than mere compromise. Without exaggeration, it’s actually the most transformative process I’ve witnessed for me and the people around me. And if we think about it, it’s not surprising: conflict occurs when things cannot stay the same, when they must change because they just don’t work anymore.

The question then becomes: how to make it a transformative occasion?

During one of my lecture about the Intercultural Conflict Resolution, I asked my students to work in pairs and figure out a way to solve a problem. The problem was a clenched fist. With a partner, one student clenches his or her fist. As a team, they need to figure out a way to unclench this student’s fist. I gave them 60 seconds to figure it out. What do you think happened? How did they get the person to unclench his or her fist? What did they do to overcome the challenges? You will be not surprised when I tell you that almost all of them used force to solve this problem. No kindly asking, no even offering money, just fight.

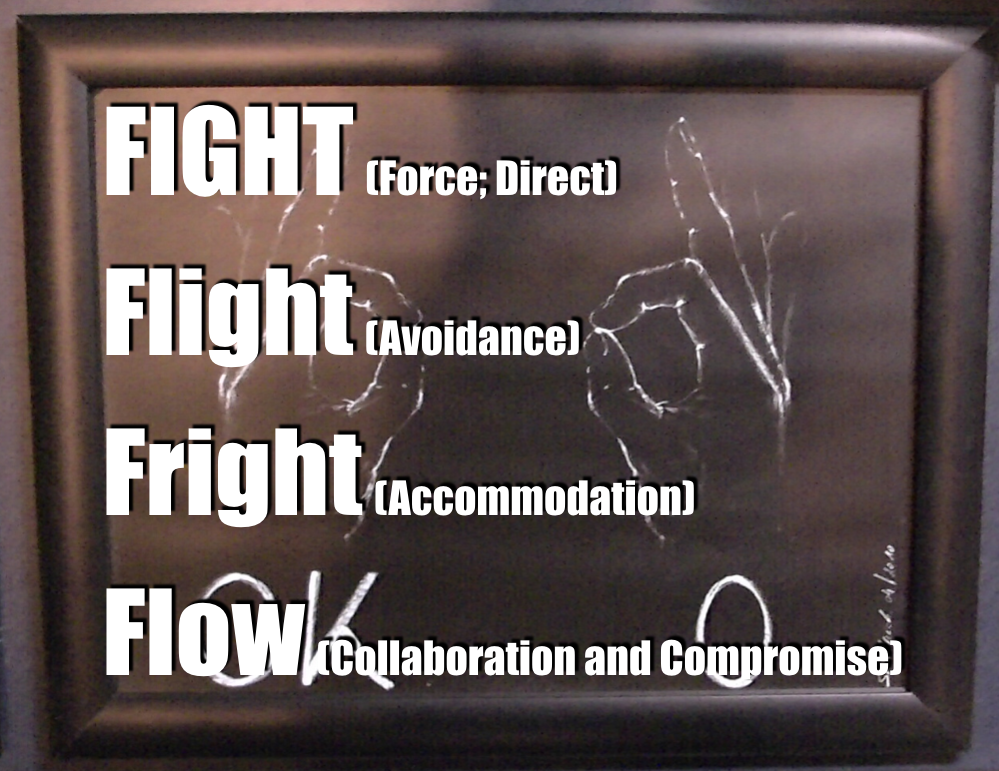

You can use threats, verbal and psychological attacks, and physical force to meet your goals; you can try to dominate and use your power over others. You can also choose not to express your feelings, needs, or ideas. You can ignore or deny your own rights and needs which allows others to infringe on them, you can get out of the way for reasons of safety and survival. When you are unable to express your feelings, needs, or ideas, even if you wanted to, you “freeze up” or feel paralyzed or powerless to do anything; you may get “run over” before you gain enough control and confidence to act.

The fight or flight response that has been determined to be an inborn genetic response that we rely on to protect us from danger. (Sichel, 2005)

In today’s postmodern world in which we live, where the complexity of our lives requires more than simple and absolute black and white answers, more alternative responses from which to draw from are needed. There are many shades of grey with subtle nuances and each choice we make of how to respond carries with it a myriad of consequences, some planned for and others unintended. Although the fight or flight response may have been very necessary many hundreds and thousands of years ago to survive a harsher world, this reaction is often very less appropriate today, when the triggers are considerably smaller and our body is therefore over-reacting. In these circumstances, fear becomes the lens through which we see the working world and we need an alternative to fight or flight—this is where the concept of “flow” is very useful. If you are willing to “flow” with the other person, by establishing rapport, by listening to other points of view, and by sharing a willingness to problem solve you can choose collaboration as your conflict resolution. You can try to express your feelings and needs and stand up for your ideas in ways that do not violate the rights and respect of the other person.

When in conflict we often become self-absorbed and focus more on the hurt, pain and injustice we are experiencing. But what if we try to be empathic toward the other and to be open-minded and curious and want to understand more deeply what makes them tick, what mental models they follow and how they might differ from our own. And it is particularly important in the intercultural context!

The basic requirements for intercultural competence are empathy, an understanding of other people’s behaviors and ways of thinking, an understanding of other people’s feelings and needs and the ability to express one’s own way of thinking.

Culture is always a factor in conflict, whether is plays a central role or influences it subtly and gently (LeBaron, 2003), and culture definitely shapes how we understand that incompatibility, what actions and reactions are seen as appropriate, and what possible solutions would look like. An understanding of culture is needed in order to understand why parties value their goals, and how they understand and weigh the costs of conflict.

Our cultural assumptions and values are hidden to us unless we consciously try to uncover them. Critical reflection provides a way to access this information. Through critical reflection, the double-loop learning process brings into question the frames of reference that are used to shape how we see, interpret and make sense of the world around us (Fisher-Yoshida, 2001). This transformational approach explores deeper levels of resolution. Rather than staying with the presenting issue, relationship issues themselves are addressed. In this approach, asking the question, “What is this conflict really about?” helps those involved shift the focus to other levels of engagement. Sense (et al., 2004) discuss a movement they call the “U Movement”. They approach transformation by identifying the importance of awareness, first in the habits we have and then at a deeper level, by how we are aware. This is something that can emerge from becoming critically reflective.

The success of our actions does not depend on What we do or How we do it, but on the Inner Place from which we operate. (Scharmer 2007)

There are so many ways to act and react, there are so many conflict resolution strategies, but in every dispute, in any conflict situations, the crucial is the opening moment, to think before acting. And however different our individual perspectives are, all of them could be also a source of creativity and innovation, when we learn a communicative process that creates a higher affinity and insight beyond the separation. This deeper and expanded understanding may in fact act as a catalyst to provoke us to alter our awareness, attitudes and behaviors, with the shift potentially being as deep as changing our meaning perspectives, as well. And this is the reason why I prefer to see conflict as a learning opportunity. We can learn about ourselves, about the others and grow up together creating peace.

Dr. Anna Storck